Legal, Matters

The family members of a murder victim, appearing at the sentencing of the convicted, taking their turns at the microphone, testifying about the impact the crime had on them.

It wasn't all that long ago that such a scene was forbidden in Michigan.

Less than 30 years, in fact.

It's also a judicial history nugget that mandatory sentencing guidelines for certain crimes didn't exist in Michigan.

Also less than 30 years ago.

Vincent Chin didn't die in vain. Says me, at least. I hope his family feels the same way.

It was about 27 years ago when Chin was beaten to death in Highland Park by a laid-off autoworker and his stepfather, just days before Chin's scheduled wedding.

He was buried the day after the planned nuptials.

Chin, a Chinese-American possibly mistaken for being Japanese, was singled out by Ronald Ebens and his stepson Richard Nitz at a bar and blamed for the fact that both stepfather and stepson were out of work.

Chin never had a chance--beaten with a baseball bat and kicked and punched savagely.

Until he died.

The case gained national acclaim, and put Detroit, again, in a bad light to the rest of the nation.

But it wasn't all for naught.

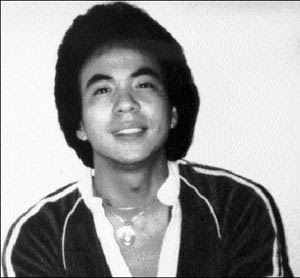

Vincent Chin

As a result of the Chin case, some changes were made in the state, in the way some legal proceedings took place.

Let's start with the testifying thing.

Ebens and Nitz received $3,000 fines each after pleading guilty and no contest to manslaughter. They didn't spend a day in prison after the trial.

Yes, a ridiculously light sentence. One that Chin's family didn't have a chance to influence.

They weren't allowed to testify at the men's sentencing, and thus weren't able to try to put, in words, the pain they felt from Chin's death--made worse because it came just before he was to get married.

So a state law was passed, allowing the families of victims to testify at sentencing.

Now for the sentence itself.

At the time of the Chin case, judges had way too much latitude in sentencing, in Michigan. So another state law was passed, with the aiding and abetting from the state Supreme Court, establishing mandatory sentencing guidelines.

No more slaps on the wrist for such a violent crime.

Earlier today, the State Bar of Michigan recognized the legal impact of the Chin case during a ceremony at the Chinese Community Center in Madison Heights.

"This dedication brings to our consciousness again the importance of educating the public about prejudice," Sook Wilkinson, chair of the state's Asian Pacific American Affairs Commission told the Detroit Free Press.

A plaque was to be presented at today's ceremony, and supporters hope to install it on Woodward at Nine Mile in Ferndale, where a small group of Asian Americans first met to discuss Chin's killing, according to the Free Press story.

A cynical person might complain, "Why does it always take someone's death to get something done?"

That person would raise a very good question.

But something was done, and that's something, because sometimes even death doesn't result in anything being done.

Right?

Vincent Chin was 27 when he was killed, 27 years ago. Today he'd be 54, and perhaps with a grandchild.

That didn't happen, but in death, Chin, indirectly, made things better for a whole bunch of people.

And that's not a bad thing, when taken in context.

Easy for me to say, I know. But not any less true.

Comments

Post a Comment

As you will...